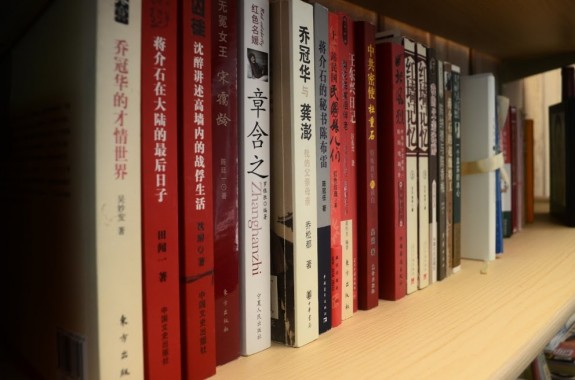

Go to any bookstore or library in China and you’ll find hundreds of novels written in boxlike characters made up of different undulating strokes and curvy lines (like this: 爱). In a large bookstore chain like XinHua, you’ll find those same books stacked alongside a section of “foreign works,” often written in English or their Chinese translations. Though Chinese may be completely foreign to people who are unfamiliar with the language, behind those shapely characters are tales of joy, betrayal, romantic gestures and family matters – themes that can be found in stories of any culture, including Western fiction.

At the same time, Chinese and Western cultures are based on very distinct belief systems and societal values (not to mention, the difference in the span of their respective histories is thousands of years apart). A concept like, say, individualism conjures up a range of emotions – or no emotions at all – depending on who you’re talking to. These differences, consequentially, are often reflected in their literature, and readers’ interpretations of books vary.

So what are some of these differences?

To answer this, I spoke with several avid readers who grew up in China but also understand English well and have experienced Western culture to some degree. It’s important to acknowledge that, aside from their cultures, everyone’s reading and life experiences are unique. But through their insight and reactions toward Western fiction, we get a glimpse of cross-cultural understanding and, ultimately, a reminder that appreciation for good books is universal.

Romance-in-the-Book

For many readers, there’s a major trade-off in reading Western fiction in Chinese: though Chinese editions are often easier to read, the author’s original tone and expression of emotions are often lost in translation. For the most part, though, the general plot and character dynamics are conveyed well.

Take “The Notebook” by Nicholas Sparks, for example. In this contemporary romance novel, the love between characters Noah Calhoun and Allie Hamilton is impeded by their class and socioeconomic differences. Instead, Allie is expected to wed Lon Hammond, a more appropriate suitor. Fred Wei, a Beijing resident, thinks it’s important for characters like Noah and Allie to follow their hearts rather than give in to conformity. He says Allie made the right decision by choosing to be with Noah – and that many people in China would agree, as more and more Chinese youth are prioritizing happiness over their parents’ satisfaction, especially when other factors like money aren’t an issue.

In reality, though, life doesn’t always end up like the books we read. Finances aren’t as easy a hoop to jump through as are family and social pressure. Wei notes that a hypothetical Noah and Allie living in China may not take the same route as the book’s characters. “The wealth gap is much bigger here in China,” Wei says. “If money and status are the only considerations here, and if this ‘Chinese Noah’ is like dirt-poor and from the countryside – or lives in a big city and cannot possibly buy an apartment there – I doubt our Chinese Allie would leave [Lon] for Noah.”

“The Notebook” isn’t the only romance novel Wei has enjoyed reading in English. It was back in high school that Wei read his first full-length English novel, “Women in Love” by D.H. Lawrence. Not only did he find Lawrence’s writing to be both provocative and philosophical, but it also possessed the right amount of subtlety. “The book blew my mind away with its candid description of sexual matters and human emotions – and it’s not done in a lewd, cheap way. It’s arousing, but not pornographic,” says Wei, now 31. Though Lawrence’s books caused controversy back in the 1900s for explicit material, for Wei, being able to read an English-written book like “Women in Love” in its original form is something to be appreciated – especially since Chinese translations may be revised due to censorship.

Wei says Chinese fiction tends to depict characters that are static and have fewer internal conflicts, while characters in Western fiction are more dynamic and complex. In that way, Chinese stories are more predictable and the motifs are often laid out for the reader. “The Western fiction that I’ve read are not so straightforward, and moral judgment is always left for the readers to make for themselves,” Wei says. “Even when there were stereotypical malevolent characters – like Rebecca [of “Rebecca” by Daphne du Maurier”] – the author didn’t draw moral conclusions by telling readers point-blank that a woman shouldn’t sleep around and taunt her husband.”

Of Political Mind

One classic historical romance novel that has garnered attention within the United States for decades is “Gone with the Wind” by American author Margaret Mitchell. This longtime favorite within the United States follows a vain young woman named Scarlett O’Hara whose well-to-do Southern family endures the economic consequences of the Civil War (1861-1865). Christin Guo, a college student in Beijing, China, says she learned about America’s Civil War from taking history in middle school. “[The war] made the slavery system abolished and contributed a lot to the development of America,” Guo says. “After I read the book, I was able to [understand] more about the problems of racial discrimination and the suffering that the war brought people.” Guo says she believes most people in China who have read “Gone with the Wind” enjoy it mostly because of its charming protagonist and her struggles with love and poverty rather than the historical context.

With a book that’s heavy with implications of politics, leadership and social order, such as the dystopian novel “Lord of the Flies” by English author William Golding, Wei says he thinks most Chinese people are inclined to interpret it more so through “the lens of human nature.” Most people living in China aren’t exposed to party politics the way Americans are, so the political significance of a novel isn’t immediately apparent, he says. In “Lord of the Flies,” a group of young boys are stranded on an island after a plane crash and create their own system of government, which only leads to savagery and even homicide.

To Wei, the many character deaths are Golding’s way of implying that the act of killing arises from dark, animalistic tendencies innate to all humans. “The twist comes in the end, when the boys are found by adults and it’s like snap! They’re back to their bright-eyed, innocent selves,” says Wei, who has also read “Crime and Punishment,” “Moby Dick,” and “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” among other novels. “I think it’s a satirical way of saying violence – though [it springs] from human nature, free of social restraint – is an adolescent, laughable abnormality if it were not so deadly, which can be put to right by more mature, authoritative people.”

Regardless of what country you’re from, he says, people who read “Lord of the Flies” are bound to find the characters’ behavior cruel and the book brutal and shocking. Similarly, Karen Xue, a graduate student at Boston University who grew up in Shanghai, China, says anyone who reads or watches “The Hunger Games” trilogy by American writer Suzanne Collins will probably have comparable reactions. Though she’s only seen the movies, she says the overall plot reminds her of World War II. “I guess with a general understanding of history and worldview, people would view [“The Hunger Games”] roughly the same, regardless of their cultural background,” Xue says.

Wei acknowledges that since he lives in a different time and place than the Western authors, he has to put aside his own cultural biases and moral beliefs, and keep an open mind while reading their books. “The beauty is in peeling away the superficial differences between the cultures and finding that, deep down, it’s all about the universalities of human nature,” Wei says.

As a recent graduate of UNC School of Journalism, Wendy Lu has written for a variety of print and online publications, including China.org.cn, The Daily Tar Heel, Raleigh Public Record and Chapel Hill Magazine’s The WEEKLY. In college, she served as the managing editor of UNC’s Blue & White Magazine and print co-editor for The Durham VOICE. Wendy is also a former publishing intern at Sleepy Hollow Books and a NaNoWriMo 2008 winner. Learn more about Wendy at https://wendyluwrites.com.

As a recent graduate of UNC School of Journalism, Wendy Lu has written for a variety of print and online publications, including China.org.cn, The Daily Tar Heel, Raleigh Public Record and Chapel Hill Magazine’s The WEEKLY. In college, she served as the managing editor of UNC’s Blue & White Magazine and print co-editor for The Durham VOICE. Wendy is also a former publishing intern at Sleepy Hollow Books and a NaNoWriMo 2008 winner. Learn more about Wendy at https://wendyluwrites.com.