Graphic Medicine is a growing subgenre among books usually shelved as graphic novels. The driver for this is, in part, modern medicine’s penchant for making everything seem frightening and incomprehensible. Graphic medicine seeks to make clear all the gobbledygook that doctors write and say to describe medical conditions to their patients.

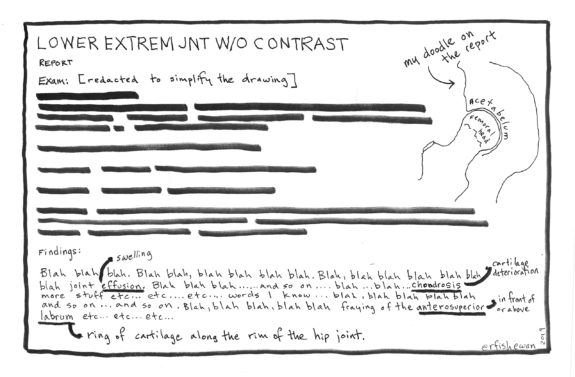

I do my own form of graphic medicine every time I get an MRI report. Above each multisyllabic medical term (chondrosis), I write its meaning in plain language (cartilage deterioration). In the report margins, I draw the bones or neural networks being MRI’d with arrows pointing to the bits giving me trouble. I still haven’t figured out what the descriptor grossly unremarkable means, though it feels like a dismissive doctor term for normal and therefore medically uninteresting. Ah, if only society considered normal as grossly unremarkable.

Neurodiversity: What’s that?

In 1998, Judy Singer, an Australian sociologist coined the term ‘neurodiversity,’ a word that signaled a shift in thinking about how and why human minds are not all wired the same. It challenged the theory that there are two kinds of brains: normal ones and broken ones.

According to this widely accepted theory that Singer disputed, broken minds needed to be fixed and by fixed I mean they needed to become like the normal ones. Neurodiversity rejects this normal/abnormal binary. As Harvey Blume noted in an Atlantic article published in 1998 (a banner year for post-modern thinking), On the Neurological Underpinnings of Geekdom: “Who can say what form of wiring will prove best at any given moment? Cybernetics and computer culture, for example, may favor a somewhat autistic cast of mind.”

I am neurodiverse. I know this now, but in 1998 I just thought I had had such a whacked childhood that it was no wonder I rarely saw the world in the same way everyone else around me saw it. My perspective was warped by all the weed I had smoked at twelve. And the acid. Or the excessive drinking that defined my early twenties. Maybe what had happened during blackouts broke my brain. Who knows? By the time 1998 rolled around, I was knee-deep in striving for normalcy—pursuing a doctorate, tenure tracking, buying a home, getting married, having a baby, all the things normal people do.

Normal: Who is? Who cares?

Too bad doing things that normal people do, doesn’t make you normal. What is normal anyhow? No, wait, I know this one. I’ve known this one my whole life. Normal is NOT ME. But back when neurodiversity was in its infancy, I still believed I could become normal. All I had to do was shed myself from myself. Then I could cover my selfless self with a kind of mirror, so I could reflect those around me. So I could become like them. Or at least appear to be like them.

Camouflage, a Behavior and a New Book of Graphic Medicine

I just read a small graphic medicine book by Dr. Sarah Bargiela, with art by Sophie Standing, whose title gave a name for what I had been doing. It’s called Camouflage. In the book, the term is used to describe what people on the autism spectrum do to appear neurotypical.

Camouflaging can extend to many other human conditions that people try to hide in an effort to fit in, be accepted, escape bullying, avoid labeling, make friends and feel human. For people on the autism spectrum who have limited neural wiring to instinctively know how to read social cues, they will mimic observed behavior in an attempt to hide their own inability to read body language and social behaviors.

Camouflage highlights this coping mechanism as it is practiced by women. After reading the slim publication, I googled the resource links provided in the back pages and eventually found an academic article reporting, in a scholarly format, the same information that Camouflage includes.

So why make a graphic medicine book? Why not just read the article?

I’m an academic, so I’ve slogged through hundreds of scholarly articles in the past twenty-five years, and I can say definitively that they contain a ton of fascinating information, but reading them is tedious and frustrating. The article, The Experiences of Late-diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype (Bargiela, Steward & Mandy, 2016), was actually one of the more readable academic articles, but as a genre they are formulaic and lack narrative tension and pretty much every other literary device that makes reading interesting. Many require an understanding of things like chi-square tests and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, terms I promptly forgot the meaning of after my one and only college statistics final exam thirty years ago.

The graphic medicine genre seeks to bridge the gap between medical gobbledygook and most human beings. Camouflage, in words and pictures, introduces the basics of autism history, theory and experience, while delving deepest into the ways in which women are often diagnostically overlooked, because they present differently than men on the spectrum.

If the two approaches to communicating medical information were food, the academic article might be a ginormous bowl of porridge, while the graphic medicine book is a delightful tray of tasty finger food, with all the nutritional bits buried (or camouflaged!) under lovely plating, scrumptious bite-sizing, and flavor. While neither offer a complete diet of autism information (gorge on NeuroTribes by Steve Silberman for that!), the party platter increases the odds that every snacker will find something worth nibbling on and they may even stick around for the main course (meaning they’ll seek out and devour more info on autism).

In this way Camouflage succeeds. It’s not exhaustively comprehensive, but it’s a great start to imagining how to live a full life as a neurodiverse human being. Reading Camouflage might also help the so-called neurotypicals (aka normal people) with their lack of empathy for those who don’t think or behave like they do. Either way, I recommend biting into this yummy little book.

Rebecca Fish Ewan, a poet/cartoonist/writer and founder of Plankton Press, teaches in The Design School at Arizona State University. She grew up in Berkeley, California, and now lives in Arizona with her family. Her cartoon/free verse memoir, By the Forces of Gravity, was published in 2018 through Books by Hippocampus. You can connect with her at rebeccafishewan.com