Happy New Year! 2021 is behind us and I, for one, am looking toward the future with plans to blossom in new ways in my life and in my writing. To that end, I’ve decided to take this column in a new direction. In my previous posts, I covered how collaborative storytelling games can aid in your world-building and how you can use them to develop characters. Going forward I will be focusing on specific games, giving you a bit of insight into what I like about them, and how I think you can use them in your writing practice.

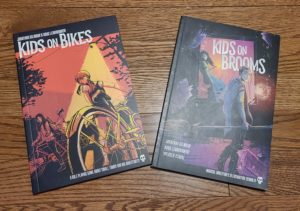

I would like to introduce you to Kids on Bikes and its magical younger sibling Kids on Brooms. These are indie games from Renegade Game Studios and Hunters Entertainment. Kids on Bikes was created by Jonathan Gilmour and Doug Levandowski, and the pair collaborated with Spenser Starke for Kids on Brooms.

Kids on Bikes

Kids on Bikes takes place in a small town where the whole table works to create together. I like this collaborative world-building because it eases the Game Master’s job in creating and populating the world, and aids in cementing the players in the setting of the game. Collaborative world-building can also be a boon to your writing because your table will flesh out parts of the world you may not have considered. Other people will make decisions that inspire your own creativity, and you’ll create something collectively that you could not have created on your own.

The idea of Kids on Bikes is that the players take on the roles of inhabitants of the small town you create together then investigate a mystery or supernatural conspiracy that the Game Master creates. Think Stranger Things or Stephen King’s It.

Kids on Brooms

Kids on Brooms uses a very similar system, but rather than the characters being inhabitants of a collectively created small town, they are the faculty and students of a collectively created magical school and the Game Master creates a magical mystery adventure for the table. Think J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter or Ursula K. LeGuin’s A Wizard of Earthsea.

The Logistics

Indie games are fun because they tend to be rules-light in their systems, favoring narrative decisions from your table. These two games are no different in that respect. The systems focus heavily on narrative drive rather than character stats and rolling the dice. One thing that I love about the system these games use is that character abilities vary widely from character to character because stats are assigned dice to roll rather than points.

Character Stats

The character stats in these games are Fight, Flight, Grit, Brains, Brawn, and Charm. When creating your character you assign each standard polyhedral die to a stat. The thing your character is best at would get your d20 and the thing your character struggles with most would get your d4. If a character fails a roll they gain an adversity token which can be spent later to boost the outcome of a roll by 1. This is used in the storytelling to show the times when someone does something outside of their normal abilities in the heat of a moment, like when a mom lifts a car off of her child in a rush of adrenaline.

The Difficulty of a Roll

The difficulty of a roll is set by the Game Master but the average difficulty threshold of a roll is between 5 and 9. This may sound like characters will always fail rolls involving their d4 stat but if the maximum is rolled on any dice roll, then that die “explodes,” meaning the player gets to roll it again and add the new result. This means that if you roll a 4 on a d4, then roll the d4 again and get a 3 your end result would be 7. There is no upper limit on the number of times a die can explode, so you just keep rolling until you do not roll the maximum. This mechanic leads to excited shouting around the table as players cheer for roll streaks and intense moments of pregnant silence while players wait with bated breath to see if their teammates succeed.

Narrative Control

Another unique aspect of these games is that narrative control passes based on the level of success or failure. In most tabletop games, narrative control lies firmly in the hands of the Game Master. Players control what their characters do, but typically their control ends where their character does. In Kids on Bikes and Kids on Brooms, narrative control shifts between the players and the Game Master.

If the outcome of a player’s roll is over the difficulty threshold by a significant margin, then narrative control switches to the person who rolled that outcome. That means they get to dictate not only how their character does something but also how the world around them responds. If the outcome of a player’s roll is under the difficulty threshold by a significant margin then narrative control switches to the Game Master, or remains with the Game Master if it were not in someone else’s hands, and the Game Master may also explain how the character reacts. This loss of character control is not for every table, but I do appreciate that these games attempt something new.

Applying It to My Writing

The area in which these games have contributed something different to my writing practice that I haven’t found in other games is in their focus on sensitivity. These games have entire chapters focused on setting boundaries for safe play and maintaining sensitivity in the portrayal of diverse characters. They recommend a session 0 before active gameplay starts where the Game Master can ask players about the subject matter they are comfortable with and the types of characters they want to play. This session also serves as a place to let players know that they can come to the Game Master with their sensitivities privately.

These games suggest an outline for these boundary-setting conversations called Lines and Veils and it was created by Ron Edwards in his 2003 game Sex and Sorcery. This activity involves players and the Game Master sharing the things that they are not comfortable having in the game at all. These “lines” are topics that should not ever be in the game. Once these borders are put in place, the conversation then should turn to topics that table members are OK with having in the game but should take place off-camera, not described in detail. These are called “veils.”

This boundary-setting conversation is helpful in writing because it not only expands your mind by thinking about things that are sensitive to others that you may not have thought to consider. Veils also give you a chance to flex your creative muscles to evoke something sensitive without being too graphic.

Kids on Brooms and Kids on Bikes also recognize that a single sensitivity conversation is not always enough to keep the game a safe space for everyone so they also encourage the use of a system called the Script Change Tool by Brie Sheldon. This is used during active gameplay to allow players to “pause” the game to give them room to deal with something that is playing on their sensitivities before the game proceeds that way, “fast forward” over-sensitive description that they do not want described in detail and to “rewind” the game to change the direction of storytelling entirely to avoid a topic they’re uncomfortable with.

Though I don’t believe that sensitive topics should be avoided in writing entirely, I do think that practices like these allow writers to consider how and why sensitive topics are used in their work.

Tell us in the comments: Do you think you’ll make use of these exercises?

Kris Hill is working on several genre fiction novels because she has difficulty sticking to writing one project at a time. In her daily life, she attempts to navigate the corporate world as a data analyst. When Kris is not working, she can be found sprawled on a couch reading or running tabletop adventures for her friends. She lives in Canada’s capital city with her husband, her best friend, and four cats.