Research: for some people, the word itself is enough to send chills up the spine. It brings back memories of term papers and case studies . . . of long hours pouring over mostly boring academic treatises and note cards . . . of bibliographies and footnotes and the dreaded decision about when to use Ibid . . . memories long since consigned to the bin labeled “that was no fun.”

For the historical fiction author, though, research is essential to the authenticity of our narratives. Whether your approach is to amass all your research before you start writing or to infuse research throughout the process—“just in time” research, so to speak—it’s the necessary grounding for this genre.

Presumably, we already know how to go about finding the facts and the historians’ insights that we need. What I’d like to explore here is a sideways look at how to have, at your fingertips, things you may find helpful when you get the inspiration for your story.

Research by Osmosis

Since we’re interested in things historical anyway, it’s probably a safe bet to assume that interest informs many things we do in our daily lives. So think about how those things you do anyway are the opportunities to gather material that may one day become part of a novel.

Reading

Is reading your thing? I’ll bet there’s historical fiction—maybe even biography or non-fiction—in your mix. You’ll glean an enormous amount of information, just from your hobby, that can actually inform your own writing. Scholars do this all the time—building on the research done by others. So why not use what you’ve already learned from your reading when you sit down to create your own story?

Antiques

Do you like antiques? Whether it’s furniture or dinnerware or jewelry or knick-knacks, the pieces you’re drawn to have a back story, either on their own or of the era they’re from. So ask about the provenance of things you admire. Facts and fodder for a future tale.

Art

Maybe you love art and never get bored wandering around museums or galleries. What a treasure trove of material! The details of the paintings or sculptures, the lives of the artists, the world in which they worked, their subjects. Talk with the docents, collect brochures, take pictures when it’s permitted, make notes or keep a journal . . . soak it all up against the time when you need details for your setting or characters or when a particular piece becomes the inspiration for your story.

Travel

If you travel, you likely visit places that speak to your love of the past. Immerse yourself in them. Take pictures . . . lots and lots of pictures. There’s no reason not to when we all have such high-quality cameras in the palms of our hands. And don’t forget to take pictures of the signage at sites you visit as well, to link the facts and the images.

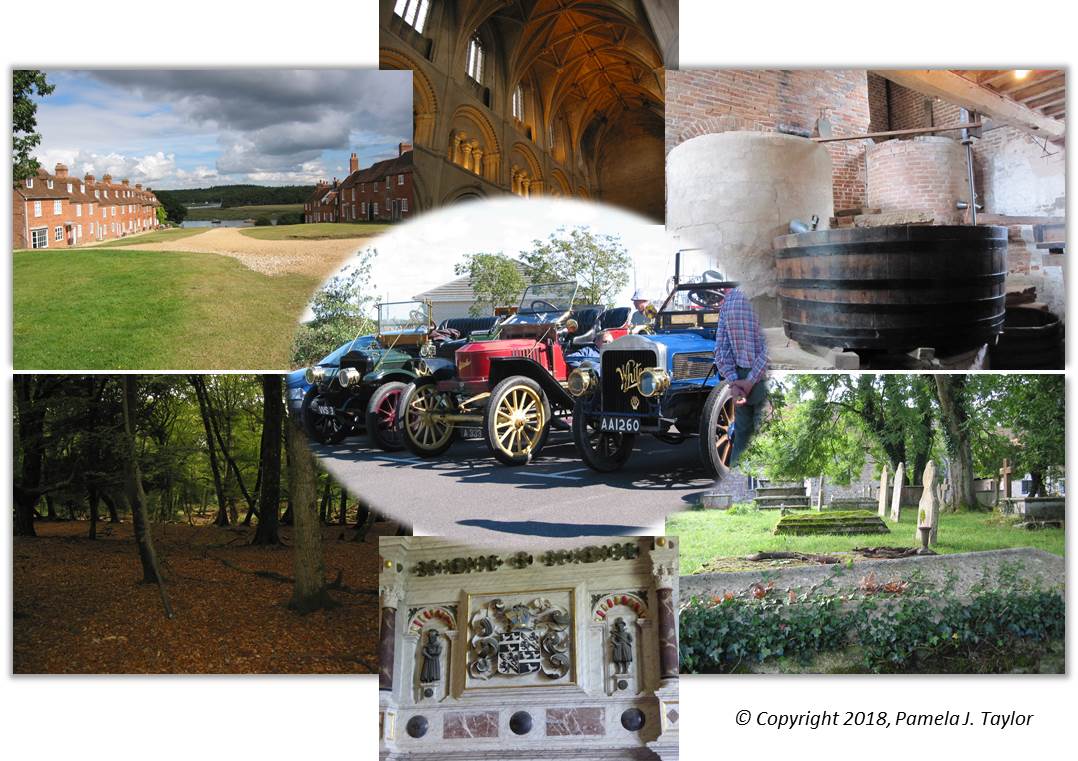

Here are just a few of the hundreds of photos I’ve assembled over the years. Center: Early 20th-century cars. Clockwise from top center: Vaulted ceiling and gallery of a 12th-century abbey; 16th-century brewing house; 14th-century churchyard; coat of arms in a 17th-century marble mantle piece; barely visible path amid fallen leaves in an ancient forest; village for workers at an 18th-century shipyard

Here are just a few of the hundreds of photos I’ve assembled over the years. Center: Early 20th-century cars. Clockwise from top center: Vaulted ceiling and gallery of a 12th-century abbey; 16th-century brewing house; 14th-century churchyard; coat of arms in a 17th-century marble mantle piece; barely visible path amid fallen leaves in an ancient forest; village for workers at an 18th-century shipyard

Some of my pictures have already been useful for descriptions in my writing. Others are still waiting their turn.

When you visit historic sites, invest in the booklets that give the details and history of the site. They’ll save you time and aggravation later. I recently had to describe details involving height of a precipice and depth of a ravine for a castle that had never been conquered. Everything I needed was right there in the booklet alongside drawings of the layout of the castle and its grounds. Another good investment is membership in historical preservation societies in places where you frequently travel. Not only do such memberships often get you reduced or even free entry to a wide variety of sites, but their newsletters and publications often include tidbits you might not have run across elsewhere.

These are just a few of the possibilities where things we do anyway are great sources of historical background.

Research, therefore, doesn’t have to be just a novel-specific thing. Sure, depending on your topic, you will quite likely need to do some focused, in-depth information gathering to accurately bring your story to life. In no way do I intend to suggest otherwise.

My point is that research is something that we who are fascinated by the past just do, almost without thinking about it. Could we find some of this stuff on the Internet? In some cases, sure. But the Internet can’t deliver how we felt and what we thought in the moment. So if we are just a bit more purposeful and attentive while engaged in what we enjoy, we’ll have a wealth of material already assembled and available when inspiration calls.

Pamela Taylor’s inspiration for her first book turned out to be that final straw that pushed her to leave the corporate world behind for the world of words and imagination. Now an author and an editor, she loves helping others polish their stories almost as much as she enjoys writing her own. She’s a member of the DFW Writers Workshop and the Editorial Freelancers Association and is in her second year on the judges panel for the Ink & Insights Contest. You can learn more about her books at secondsonchronicles.com, and about her editing services at editing4you.com.

Pamela Taylor’s inspiration for her first book turned out to be that final straw that pushed her to leave the corporate world behind for the world of words and imagination. Now an author and an editor, she loves helping others polish their stories almost as much as she enjoys writing her own. She’s a member of the DFW Writers Workshop and the Editorial Freelancers Association and is in her second year on the judges panel for the Ink & Insights Contest. You can learn more about her books at secondsonchronicles.com, and about her editing services at editing4you.com.