Trigger warning—contains memories of sexual abuse

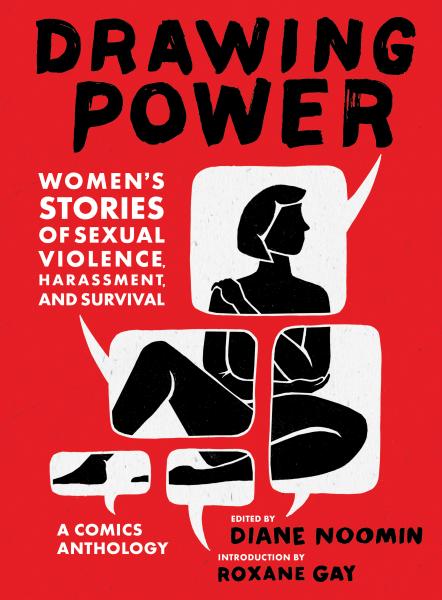

I’m reading Drawing Power, a new comics anthology (edited by Diane Noomin with an introduction by Roxanne Gay). Inspired by the #metoo movement, sixty-three comics artists, including Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Liana Finck, Ariel Schrag, Una, and Emil Ferris tell their stories of sexual harassment and abuse. I was excited when I found out about this book, pre-ordered it through my local indie bookstore and eagerly awaited the release this September. It sits on my bedstand and I read a bit of it each night before falling asleep. Probably not the best strategy.

I’ve never been comfortable calling myself a survivor of sexual abuse. Or a victim. For many years I just pretended what happened to me as a child was all part of growing up in the seventies. Peace, love and all that. In my twenties, I rationalized that sex had been a weapon used to overpower me as a child and now I held the weapon and was going to make good use of it. As if my litany of childhood abuses earned me the necessary know-how to break my boyfriends’ hearts. Yay me.

The #metoo movement coincided with the release of my cartoon memoir, By the Forces of Gravity. To illustrate the dark path my life was taking by age twelve, so readers could appreciate how urgently I needed the light of my friendship with Luna (the subject of the memoir), I drew one of my abusers in this story. The drawing of him saying “pussy” is the creepiest cartoon in the book. Altogether, I drew this man six times, which gave me some relief from the residual shame that had lingered in me for over forty years. Bringing hidden shame into the light through art can destroy it.

So why is reading Drawing Power a trigger for me now?

For that matter, why are all the revelations of the #metoo movement triggering?

Wrestling With Trauma Through Art

I had a bike accident a few weeks ago and had to get an x-ray of my skull to make sure it was alright. It was, but while the doctor was showing me the film, she pointed to a thick spot on my skull and explained that this was from a past injury. Turns out, trauma transforms your bones. Permanently. This is how it feels to be a person who has endured sexual abuse. It transforms your bones, your being, your soul. The best way I’ve conjured to process the trauma—much better than my twenty-something-self’s plan to subdue all my dork boyfriends with my mad sex skills—is to turn the memories into art.

Drawing Power is all about this impulse to wrestle sexual trauma into submission through graphic storytelling. Which is why I love it. Which is why it pains me to read it. Which is why I haven’t yet finished it.

When I can distance myself from the book’s content, I can enjoy the variety that comics anthologies offer. I love studying the line work, use of color, panel choices, all the components that make graphic storytelling such a compelling art form. Usually I can enjoy the technique while I’m immersed in the story, but Drawing Power challenges this multitasking way of reading. There are sixty-three stories, each one unique in the details, yet united by the common theme.

Reading this collection, I’m reminded again and again that the world is full of predators, mostly males, who violate younger/more vulnerable people, mostly females. The females are then burdened with shame and loss, while the men generally move on with their lives, their bones no thicker than before. This is what triggers me. I study history. Stories of rape and sexual violence are as old as humanity. There are countless paintings, Greek urns, plays, poems, television shows, films, songs, and now comics that chronicle sexual abuse.

Here’s my question: Why can’t men just stop sexually abusing people? Nobody wants it. No One! Sexual violence is not a secret fantasy for women. Abusers aren’t teaching young women the ways of love. It’s not just locker room humor. Sexual violence is the power play of cowards and the world is sick of it.

The fact that people can process their sexual traumas enough to build meaningful lives afterwards is not evidence that rape and other forms of sexual violence are no big deal, just guys goofing or misunderstanding signals. It is a testament to the bad-assedness of the people who have been abused.

The Necessity of Nuance

Drawing Power offers proof of bad-assedness, not so much in stories structured on the hero’s journey model, hard challenges followed by victories and clear conclusions. What both bothers me and feels familiar is the way so many of these stories just exist on the page. This terrible frightening damaging thing happened, the end. It’s irksome not to have these stories end with a Wonder Woman victory, one foot on the back of a subdued oppressor who lies on the ground, snugly bound by the Lasso of Truth. I’m irked not because I want this victorious ending, but because I know this is not how trauma ends. It lingers. It’s messy. As Caitlin Cass’s story, “Surprise Bogs” notes, “It deserves nuance.”

I am trying to read Drawing Power with attention to nuance. I try to quiet my mind, so I can hear the stories and not my reaction to the stories. It’s hard to peel away decades of internal protections constructed to minimize sexual trauma, my own and the trauma experienced by other people. It’s hard, but not impossible, and worth the effort. Drawing Power is not an easy beach read. It was never meant to be. Instead, it offers light to shine on our dark secrets, courage in numbers saying “this happened” again and again, so we can find a collective voice to say “never again.”

Rebecca Fish Ewan, a poet/cartoonist/writer and founder of Plankton Press, teaches in The Design School at Arizona State University. She grew up in Berkeley, California, and now lives in Arizona with her family. Her cartoon/free verse memoir, By the Forces of Gravity, was published in 2018 through Books by Hippocampus. You can connect with her at rebeccafishewan.com