My kids will be officially young adults in a few weeks, when my son turns eighteen. This threshold into adulthood has stirred up memories from their early childhood. How I sang nursery rhymes to my daughter and had to change the genders of all the heroes in her bedtime stories as I read. How my son at five would only let me read Lego catalogs verbatim to him at bedtime (“Fire Station, ages 5-12, 600 pieces. This fire station has everything you’ll need to save the day…”).

Reading aloud is gifting language to children. Stories emerge on the pages with pictures and words (even in Lego catalogs). My fondest memories from my own childhood are listening to my dad speak like Gollum as he read The Hobbit around the fire on camping trips. Books were magic carpets transporting me to fantastical lands full of elves and ogres. Words and pictures create these magical places.

Words also interpret the real world for us. They tell the truth. They carry their own origin stories in their bones. They dwell in books. Dictionaries are cities of words.

Reasons to Love Dictionaries

I’ve always been fascinated by dictionaries. The fat tomes that lay open at the public library like magic spell books. They harbor a language’s memory. The Oxford English Dictionary, in particular, has held my deepest interest, so much so that I read Ammon Shea’s memoir about reading the OED (of course, called Reading the OED) and both of Simon Winchester’s books on this dictionary (The Professor and the Madman and The Meaning of Everything).

Dictionaries are living documents. That they grow with time, acquiring new words from other languages (bonsai) and adding new words crafted to describe inventions or discoveries (television and radioactive). As a hoarder of things, it never occurred to me that a dictionary would purge its pages of words. Afterall, slubberdegullion is still in my 1971 edition of the OED. I thought no words could be deported once they had secured residence in these literary grimoires, least of all from the OED, a dictionary that boasts of its historical trail of quotes that reveal each word’s print origins:

“1660 Beaum & Fl. Custom of Country Iii, Yes they are knit; but must this slubberdegullion have her maidenhood now?”

Once a word, always a word, right?

Not. True. At. All.

The Lost Words

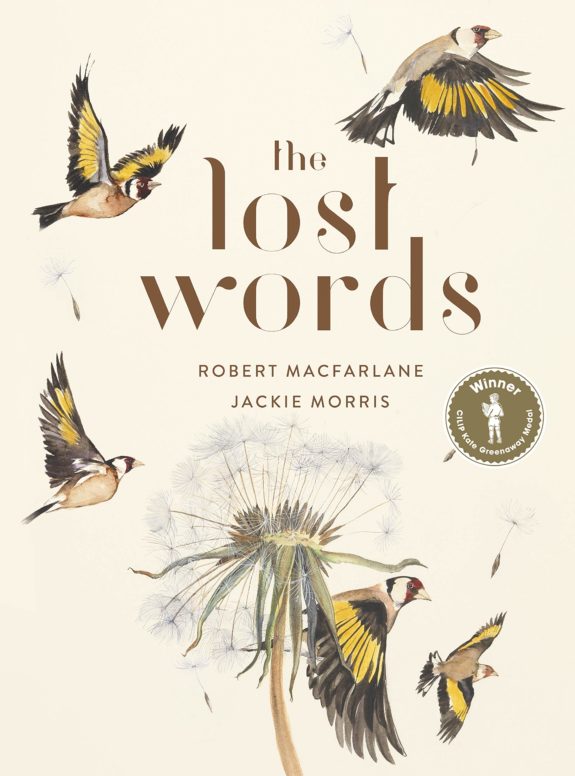

The Lost Words is a collaboration of text by Robert MacFarlane, a dedicated protector of words from nature, and illustrator Jackie Morris. This beautiful book collects words recently purged from the Oxford Junior Dictionary (like the OED with training wheels). All of these words name life in the natural world, among them wren, bramble, kingfisher, otter, acorn.

Acorn…no more!

How can a child move through life without the lessons contained in the acorn?

Or the otter?

In the introduction, MacFarlane describes the book’s text not as poems, but as spells “that might just, by the old, strong magic of being spoken aloud, unfold dreams and songs, and summon lost words back into the mouth and the mind’s eye.” Each spell includes paintings by Morris that spill over the pages, dynamic watercolors, some with gilded backgrounds, that reveal not just what a plant or animal looks like, but how it lives.

I ordered The Lost Words online and paid no attention to the dimensions, expecting it to be book-sized. You know, the kind you can stow in a bag to read on a bus or on a bench in the park. This is not that kind of book. Measuring 11 x 15 inches and hardbound, it is clearly designed for reading aloud to children. As I opened the giant cover, I imagined a classroom of kindergartners sitting criss-cross-applesauce on the floor in front of me as I read aloud to them:

“I am ivy, a real high-flyer.

Via bark and stone I scale tree and spire.

You call me ground-cover; I say sky-wire.”

Wait, what! Ivy is a lost word? Preposterous!

Words in the Digital Age

If my kids were still kids, I would read The Lost Words to them. I’d even sing the words to my daughter. The 21st-century has brought us wondrous inventions—lamps you can talk to, cars that drive themselves, a printer that can make a hat out of chocolate while you wait—all super necessary. But these digital distractions also enable us to remove ourselves from the natural world. We’re forgetting how to navigate without Siri. How to make things with our hands. We’re losing the words to describe that little flower in the grass, you know the one, yellow, what’s it called again? Oh yeah…dandelion.

Dandelion! It’s one of the purged words! Scandalous!

These words were deleted from the Oxford Junior Dictionary to make room for words like blog, broadband, chatroom and voicemail. Go ahead, try to write a magic spell that reads like poetry and inspires gorgeous watercolor paintings, using only these new words. Unbearable to even imagine it.

The Impact of Lost Language

The Lost Words covers only 20 of the deleted dictionary entries. A 2015 article by Alison Flood in The Guardian (“Oxford Junior Dictionary’s replacement of ‘natural’ words with 21st-century terms sparks outcry”) notes more, including hamster. Hamsters are the go-to creature for helping children learn to care for other living beings. This article centers on a letter written by 28 authors, MacFarlane among them, voicing concern for the impact of these vanishing words:

“There is a shocking, proven connection between the decline in natural play and the decline in children’s wellbeing.”

With the influx of digital culture, the impacts on children’s contact with nature has been measured and found wanting. Richard Louv’s 2005 book Last Child in the Woods, alerted us to what he called nature-deficit disorder. The Lost Words is a compelling poetic companion book to Louv’s more journalistic call-to-attention publication. While concern for children’s contact with nature is not limited to the digital age—Rachel Carson published an article on cultivating a child’s wonder of nature in a 1956 issue of Woman’s Home Companion magazine—but the concerns feel more urgent. One fear is that children raised without a vocabulary for the natural world will grow up to be adults without empathy for its ecosystems, for its flora and fauna, for its life.

Without this empathy, what will compel them to protect the Earth?

Research supports improved childhood health with increased contact with nature. Among benefits noted by the Natural Learning Initiative are: reduced stress, less ADD symptoms, improved eyesight, and enhanced cognitive abilities.

I’d recommend reading The Lost Words aloud to a gaggle of children, under a tree, in a garden, or beside a brook. Who knows, you might spy a heron winging over the heather or a weasel in the woods. And you’ll all know how to name these wonders of the glorious green earth.

Rebecca Fish Ewan, a poet/cartoonist/writer and founder of Plankton Press, teaches landscape design in The Design School at Arizona State University. She grew up in Berkeley, California, and now lives in Arizona with her family. Her cartoon/free verse memoir, By the Forces of Gravity, was published in 2018 through Books by Hippocampus. Currently working on a craft book on drawing for writers. You can connect with her at rebeccafishewan.com or Instagram @rfishewan