Welcome back to The Messy Middle, where we focus on crafting complex characters and building dynamic worlds that connect with readers from marginalized communities. In a previous post, The Messy Middle: Cultural Content Fender Benders, we explored a framework for responding to readers’ concerns about representations in our writing. In this post, we will continue reflecting on the potential negative impact of our work by focusing on book bans in the United States.

Honestly, it’s very frustrating that Iowa, my home state, has made national news for passing a law that seems to “level up” efforts to suppress speech by adding governmental oversight for book banning. This bill essentially requires Iowa school libraries and school staff to remove/ban books that are (ambiguously) deemed inappropriate for children, or risk facing punitive repercussions. There are multiple threads to pull when examining the general nature of book bans. In this post, we will attempt to connect the obvious (to some) political motivations of book bans to what I consider to be the core of the issue, society’s fear of change and loss of power.

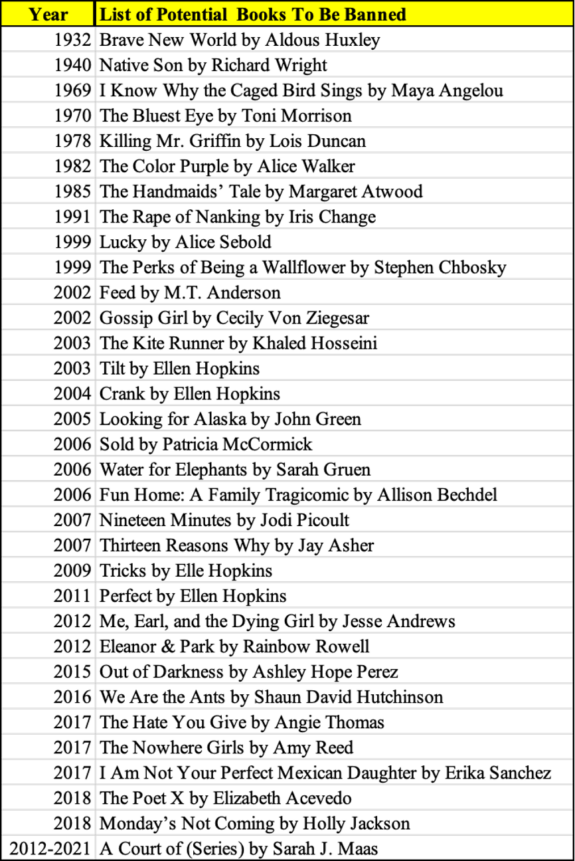

We will use the proposed book ban within a community in Spencer, Iowa as a case study. Spencer, Iowa has an approximate population of 11,000 people and is in the northwest corner of the state, bordering Minnesota and Nebraska. Out of the five schools, the district has one middle school and one high school. Within the district, 10% of the students identify as nonwhite and 28% have families with low income. The list below contains the specific books that may be banned to comply with the new “Parental Rights” Iowa law that was passed in May and enacted two months later on July 1 of this year.

*I have ordered the books by the year they were published.

*There are varying forms of this list circulating in the community.

Misdirection

The books proposed were published between 1932 and 2021. Nearly 75% of the authors on this list are White women and more than half of the novels are from the young adult (YA) genre. A quick internet search reveals that all the titles listed have been individually banned by other states or have appeared on book ban lists. On the surface, this seems to be due to the depictions of sexuality, coarse language, substance use or abuse, or violence. However, after drilling down a little deeper, it became more apparent in most cases that these novels were banned because they made some parents, conservative politicians, and religious groups feel uncomfortable about the marginalized communities and experiences on which they were centered. Some of the common themes were related to:

- Substance use and abuse

- Depression and anxiety

- LGBTQIA+

- Race and ethnicity

- Violence

- Illness

- Homophobia

- Sexism

- Racism

- Stereotypes

- Grief and loss

- Economic inequality

- Emotional, sexual, and physical abuse

- Gender

While book bans have been packaged as an effort to “protect children” from inappropriate “descriptions or visual depictions of sex acts,” I find it ironic that they are not protected from being forced to give birth, depending on the state and instead are being “protected” from reading about things that lead to pregnancy. The true goal of this ban is to block content that centers on LGBTQIA+ and marginalized experiences.

As we continue to have meaningless online reaction wars about the perceived loss of rights, insignificant occurrences of “cancel culture,” “wokeness,” and the “PC police,” a record level of legislation continues to be pushed through to strip marginalized communities of their actual rights. Book bans not only illustrate what systematic discrimination and political power can look like, but they also provide us with tangible evidence of our growing fear of and reluctance to accept inevitable change and difference in our nation.

We Can Do Hard Things

In her 2020 best-selling memoir, Untamed, author Glennon Doyle recalls how seeing the mantra “we can do hard things” written on a classroom banner became the perfect reminder to summon her courage to overcome addictions. In Untamed, she reminds us of this mantra as she reflects on the urgency and importance of having discussions with our children about sexuality and pornography.

In the chapter titled “Woods,” Doyle reflects on a chat with a close friend and her friend’s reluctance to talk with her son about his frequent pornography consumption. Glennon reminded her friend that it’s normal to feel discomfort and hesitancy when navigating conversations about sexuality and other uncomfortable realities with our children, but that she cannot leave her son “alone in the woods” to figure it all out. Doyle tells her friend:

“We don’t have to have answers for our children; we just have to be brave enough to trek into the woods and ask tough questions with them.”

As a parent, I want to acknowledge the lack of control most of us feel while raising children in an internet and smartphone-filled world. It can be tempting to try to avoid the amount of toxicity and danger that exists in the world by blocking everything, but we do a great disservice to children by sending them into the world without the knowledge, skills, and tools to survive.

Answering The Call

If you believe that book bans are wrong, I am challenging you as a writer to speak up and get involved (beyond a social media post), in your community, state, or at a national level. Many local and school librarians are in desperate need of support with this issue. I have cited a few sources at the end of this post that can provide more context about book bans.

Lastly, we will end by reconnecting with the first post, It’s Messy in the Middle: Answering the Call for Diversity, where this column began two years ago. Looking back, we consider if and how we can answer the call for diversity in our writing, which is still an urgent and pressing issue for the publishing world. I still believe that as writers, we must answer the call for diversity in our writing by illustrating the intricate humanity of underrepresented and marginalized identities in our stories.

Works Cited

Exman, B. (2023) This summer, I became the book-banning monster of Iowa, The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/01/opinion/book-ban-schools-iowa.html (Accessed: 18 September 2023).

Harris, E.A. and Alter, A. (2023) Book bans are rising sharply in public libraries, The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/21/books/book-ban-rise-libraries.html?campaign_id=9&emc=edit_nn_20230922&instance_id=103378&nl=the-morning®i_id=114195098&segment_id=145410&te=1&user_id=2f6e6326bf23cd7ccab653496bf26e6b (Accessed: 22 September 2023).

Melton, G.D. (2020) ‘Woods’, in Untamed. New York: The Dial Press, pp. 175–177.

Schmidt, A. (2023) ‘19 books pulled from Mason City school libraries’, The Gazette [Preprint]. Available at:

https://www.thegazette.com/k/19-books-pulled-from-mason-city-school-libraries/ (Accessed: 18 September 2023).

Colice Sanders is a blogger and diversity, equity, and inclusion facilitator. Colice writes nonfiction, poetry, and memoir. Her blog, A Reason to Rise, chronicles her journey of radical self-acceptance through the lens of childhood trauma.