With so many books on the market (upwards of a million published each year), maintaining loyal readers continues to be a priority for authors. We not only need to get them reading our books, we’ve got to keep them reading—to the last page and onto whatever else we’ve written. Discussions abound on exactly what magical formula will accomplish this, but I truly believe it comes down to one simple element: empathy.

To engage readers, we need them to empathize with the main character. They need to care about him or her and whether or not they succeed. This is often accomplished when we can convey the character’s emotions in a way that engages the reader’s emotions; get them feeling what the protagonist is feeling. And the best way to do this is by compellingly showing (not telling) the character’s emotional state.

Readers are not pulled in by the telling of emotion because they’re simply being fed information. He was sad. She felt angry. Telling creates distance between the reader and the character, which is exactly the opposite of what you want. To pull readers in, we need to bring them close. Invite them into the story to share in the character’s experience. Showing is the way to make this happen. And there are five vehicles you can use to effectively show character emotion—all of which already play a part in your story.

1) Dialogue

We use dialogue to articulate our ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and needs, all of which are driven by our emotional state. What we feel always propels us, but it’s rare to refer to those feelings directly in conversation. So while dialogue is a proven vehicle for sharing a character’s emotions, it rarely should do so alone. To convey feelings well, a writer should also utilize the nonverbal elements of conversation: vocal cues, body language, thoughts, and visceral reactions.

2) Vocal Cues

These are shifts in the voice that supply readers with valuable hints about the speaker’s emotional state. In conversation, there isn’t always time to think about how to react, so while a person might disguise their true feelings by choosing their words carefully, their tone of voice or the flow of words won’t be as easy to control. Hesitations, a voice that changes tone or pitch, words that suddenly slide out faster—all of these are terrific indicators that a character’s emotions have changed and there’s more to the exchange than meets the eye. Vocal cues can be especially useful for showing the feelings of a non-point-of-view character, since, in most written viewpoints, their direct thoughts cannot be shared with the reader.

3) Body Language

This is how our bodies outwardly respond when we experience emotion. The stronger the feeling, the more we react and the less conscious control we have over movement. Because characters are unique, they will express themselves in a specific way, making the writer’s options for showing emotion through body language and action virtually limitless.

4) Thoughts

Thoughts act as a window into the mental process that corresponds with an emotional experience. A character’s internal monologue is not always rational and can skip from topic to topic with incredible speed, but utilizing that mental response to express emotion is a powerful way to convey how they see their world. Thoughts also add a layer of meaning by illustrating how people, places, and events affect the point-of-view character and can help showcase their voice.

5) Visceral Reactions

These are the most powerful form of nonverbal communication and should be used with the most caution. These internal sensations (heart rate, lightheadedness, adrenaline spikes, etc.) are raw and uncontrolled, triggering the fight-flight-freeze response. Because these are instinctive reactions, all people experience them. As such, readers will recognize and connect with them on a primal level.

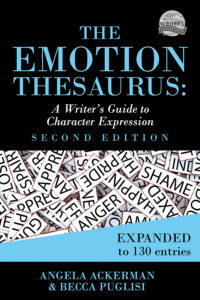

To make your character’s emotions crystal clear for readers, try a combination of these vehicles. Showing emotion takes a bit more effort than telling, but when it’s done well, it can pay off in heightened reader engagement and increased empathy for the character. So it’s definitely worth the effort. More information on this subject and others pertaining to character emotion can be found in the second edition of The Emotion Thesaurus.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of books for writers—including her latest publication: a second edition of The Emotion Thesaurus, an updated and expanded version of the original volume. Her books are available in multiple languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world. She is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge with others through her Writers Helping Writers blog and via One Stop For Writers—a powerhouse online library created to help writers elevate their storytelling.