None of us get to choose our own names—well, except for those rare few who, as adults, opt for a legal change of moniker. But now you’re a writer and what your characters will be called is entirely in your hands. Happy day! You finally get to use all your favorite names for your favorite characters. Well, a lot of writers do. But for those of us who create historically based narratives, there are some constraints—Brittany, Jayden, Dakota, or Savannah would be conspicuously out of place any time before the late 20th century.

For this article, I’m confining the discussion to names of European or Slavic origin and hope that covers a broad range of the requirements for this community. Other cultures certainly have their own sets of historical constraints, but I’ve not done the research to be able to present them here.

It’s a Matter of Time . . .

. . . and place and language . . . and don’t forget religion.

Some names seem to have been with us in more or less the same form for more than a millennium. Names like John, Phillip, Mary, Samuel, Margaret, Peter—and their equivalents in other languages—have been in use since at least the Middle Ages. This most likely stems from the Judeo-Christian heritage of the geographic area in question.

Other names that were common in medieval times, for example, have either disappeared or evolved into a more modern spelling and/or pronunciation. These days, one doesn’t run into guys named Fulk or Drogo or Basewin, or women called Hermesent, Geva, or Estrilda. However, if you meet a man named Everett, it’s likely that his medieval namesake was called Evrart or Everard. And today’s Evelyn might be a family name handed down from a 12th-century ancestor called Auelin or Avelina.

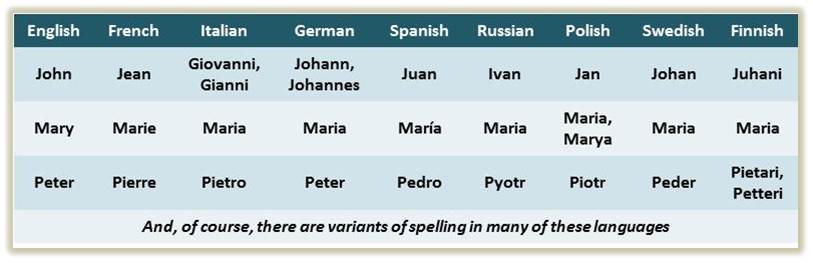

One might argue that place and language are just two different ways to reference the same influence, but I suggest there’s a distinction. Language is the easy one. Let’s take a few of those old but commonly used names:

These are just examples from some of the so-called “modern” languages. Depending on where your story is set, you may need to find names from more uncommon languages, such as Breton, Welsh, Gaelic, Basque, Catalan, and the like. Some might be equivalents such as Dafydd (David in Welsh) or Joan (John in Catalan) while others may be unique to the language such as Kenza, a Cornish feminine name, or Corentin, a Breton masculine name.

If your novel is set during the period of the Roman Republic and early Empire and your characters are Romans, the names will be Latin, of course. And the masculine names will be what we consider straightforward—a given name plus a family name, as in Marcus Aurelius. But what about the women? They would be known by the feminine form of the family name—the daughter of Marcus Aurelius would be called Aurelia. And what if there was more than one daughter? The lesser one would be Aurelia Minor. Usually, this applied to the younger daughter, but other criteria of “importance” were sometimes used. In the later Empire, there was more variety in women’s names, but some families still followed the older tradition.

In some places (the Slavic tradition, in particular), all children carry their father’s given name as a patronymic. (This bears some similarity to the pattern in the Anglo-Saxon tradition where the son of a man named Richard came to be called John Richardson.) The patronymic, however, is not the surname but a second given name, as in Pasternak’s Yuri Andreyevich Zhivago – Yuri, son of Andrei, of the family Zhivago. It was quite common for an individual to be addressed by the given name plus the patronymic, so this is important to consider in creating dialogue.

Don’t forget, too, that in Russian, surnames have a gender-specific form. Alexei Karenin, but Anna Karenina. Ivan Petrov, but Ekaterina Petrova. Patronymics, too, are gender specific. So Alexander Petrov’s children would be Ivan Alexandrovich Petrov and Ekaterina Alexandrovna Petrova.

When Europeans began migrating to the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries, their tradition of names migrated with them, so 17th-century French names would also be found in eastern Canada and in Louisiana. And don’t forget later migrations that brought, for example, German traditions to Texas. For stories set in the US, in particular, ancestry becomes a fifth dimension to consider. Its influence on given names tends to dissipate, however, after the first generation for many immigrant communities, but the surnames, of course, remain.

And then there’s that religion element. In the Roman Catholic tradition, saints’ names have always been popular. When the Protestant Reformation came along, a new trend in names emerged: virtue names that parents, presumably, hoped would shape the characters of the children to whom they were given. Women might be called Charity or Comfort or Patience or Verity. A man might be named Creed, Justice, Increase, or Valiant. Such names were particularly popular with Puritans, but their use wasn’t limited to the Puritan sect. Oddly, there seem to be far more virtue names for women than for men.

Finding Appropriate Names

It doesn’t take much Googling to come up with multiple sources for names for the era and setting of your story. A search string with time and place will turn up numerous lists for you to choose from, many with explanations of the meaning of the names and some that are actually extracts from government or church rolls of the time. When looking for medieval Nordic names, I even found a site that explained how names of both people and places were constructed in that part of the world, so you could actually build your own name.

In the foregoing discussion, I’ve focused more on given names than on surnames, but the internet sources for period—and setting—appropriate surnames are equally plentiful. Don’t forget that the form of surnames in some places may be related to a person’s station in society. In Britain, for example, after 1066, aristocrats most likely had Norman surnames such as “de Beaumont” or “de Carteret” while the common folk or peasants would have surnames from the Anglo-Saxon tradition; and the use of “von” or “zu” in German names indicates nobility. (For those interested in such details, “de,” “von,” and “zu” are called nobiliary particles—another internet research rabbit hole you can go down.)

In summary, know your characters first: when and where they lived, their beliefs, their station in life. Then go in search of wonderful names for them. One thing is certain: you’ll find a wealth of choices and likely some new favorites to bestow on the characters you love so that they feel like truly authentic inhabitants of your story world.

Pamela Taylor’s inspiration for her first book turned out to be that final straw that pushed her to leave the corporate world behind for the world of words and imagination. Now an author and an editor, she loves helping others polish their stories almost as much as she enjoys writing her own. She’s a member of the DFW Writers Workshop and the Editorial Freelancers Association and is in her third year on the judges panel for the Ink & Insights Contest. You can learn more about her books at secondsonchronicles.com, and about her editing services at editing4you.com.