Somehow bad guys and gals are in many ways more challenging to create than our so-called heroes or heroines. This is an area of your writing that invites you to stretch yourself, to play with multiple violations, remembering that you will fall in love with this character, and you will have to manage, at the end, to get your villain to a better place, even if it just means gone.

Make The Level of Evil Fit Your Genre and Category

There is a sliding scale of evil, all the way from the relatively harmless banker Mr. Babcock in Auntie Mame, whose greatest sin is having no sense of humor and sending little Patrick off to boarding school away from his crazy aunt, to the grotesquely evil Misfit in Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” He is an unrepentant murderer who remarks, “No pleasure but in meanness,” right before he shoots an old woman. Your badness quotient will have to be commensurate with the customs of the genre you’re working in.

Make Your Villain A Quick-Change Artist

Keep in mind that villains can say anything they want, they can violate social norms (and do all the time), they laugh at everybody who seems to think the world has meaning and a moral purpose. And they have no boundaries. They are real shapeshifters, shedding their skin as much as they like. Thackeray once described Becky Sharp’s career as “resembling the slitherings of a mermaid.” They can change, and they often are forced to. Your villain may start out as a truly awful person, like Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre, but later turn out to be heroic, to have learned something, and to do a 180-degree turn.

Pay Special Attention to Physical Appearance

Your villain should be physically memorable, unusual, and provocative. There is often something off or extraordinary in their eyes, in their looks, even in their souls. Beautiful or ugly, their presence operates strongly on other people to the point that we sometimes can’t tell which they actually are –– hero or villain, possibly both. At the beginning of Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff cuts a genuinely frightening figure, cruel and sadistic, and yet in his sadness and tormented love for Cathy, he grows into a richly dimensional man who is in no small part a victim. He is one of a long line of jolie laide figures, whose inside and outside provide a twisted mirror of each other. As one of the archetypes of the cosmic mysteries, your villain can and should be a mixed figure indeed.

Make Your Villain A Special Kind Of Sexy

About sex––these characters can be quite alluring, and here you are free to indulge yourself in the extremes. While writing Jenna Takes The Fall, I realized that we were going to have to see the goings on between the heroine and her very complex, difficult lover, Vincent Macklin Hull, the true villain of the piece. Her later actions toward him make sense only when you know how intensely he has aroused her early on, despite his frequent criminal behavior.

Hull is a man of 59 to Jenna’s 24. He is an art collector, a father, the head of a thriving business empire, which he inherited from a bunch of “seriously competent bastards.” I wanted to have his first seduction of Jenna take place near the pool by his weekend house in Water Mill, Long Island, and it had to be sexy. How else account for their subsequent relationship? How to make him attractive, lovable, caring, even if it’s merely timebound, opportunistic, driven by lust and boredom?

This was a juicy problem, and if you read the book, you’ll have to decide how well I did. I once knew a genius advertising man, Lee Clow, who said, “If an idea doesn’t scare you, it’s probably not an idea at all.” This one scared me plenty.

Have Fun With The Darkness

Above all, if we are being brutally honest, villains allow us to roam around in that shady side of ourselves––normally kept in check––that wants to rip things apart, tear down the walls, or just plain go nuts, like Amy Elliott Dunne in Gone Girl. Such a character is often quite witty, because laughing at society is her gig. She’s Hyde to the distinguished Dr. Jekyll. She’s what Edgar Allan Poe called “The Imp of the Perverse.” So this is the place to get down with your own bad self and have some good nasty fun.

In The End

You are never more naked on the page than in the worst moments of your villain. Some readers will love your character, a few will hate him/her, and several will say there’s clearly something wrong with the author. They will question your talent, your taste, and even ascribe to you vices you don’t actually have. They will be shocked, I tell you, absolutely shocked! Congratulations. You’ve succeeded.

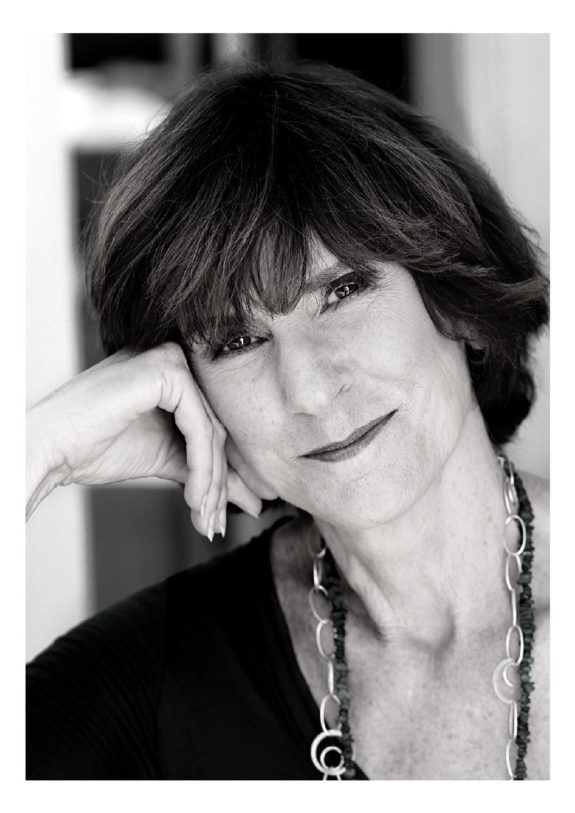

A. R. Taylor is an award-winning playwright, essayist, and fiction writer. Her debut novel, Sex, Rain, and Cold Fusion, won a Gold Medal for Best Regional Fiction at the Independent Publisher Book Awards 2015, was a USA Best Book Awards finalist, and was named one of the 12 Most Cinematic Indie Books of 2014 by Kirkus Reviews. She’s been published in the Los Angeles Times, the Southwest Review, Pedantic Monthly, The Cynic online magazine, the Berkeley Insider, So It Goes―the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library Magazine on Humor, Red Rock Review, and Rosebud. In her past life, she was head writer on two Emmy-winning series for public television. She has performed at the Gotham Comedy Club in New York, Tongue & Groove in Hollywood, and Lit Crawl LA. You can find her video blog, “Trailing Edge: Ideas Whose Time Has Come and Gone” at her website, www.lonecamel.com. She lives in Los Angeles, CA. You can find her on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Vimeo.