When you are writing a memoir, you spend a lot of your time excavating a past that is often elusive. To bring a memory to life on the page, you have to call up all the myriad details that filled it with emotion and meaning at the time, and the full force of any memory can’t be made to appear by a click. We don’t walk around with our heads full of the vivid past. We pack it away to get on with our lives. Moreover, we may intentionally bury some memories, those that were painful, humiliating, or frightening. We may even forget having stowed memories away. When the time comes that you need those memories, you may well have misplaced the key.

What is forgotten, however, isn’t gone; our missing memories are stored somewhere in our brains. We just have to find our way to them. All sorts of chance things can trigger memories to break through. For Proust, it was famously the taste of a madeleine cookie dipped in linden tea. It could be a phrase of music, the smell of a cellar, or a voice.

But a writer cannot leave recall to chance; you need to provide the trigger yourself. It would be dandy if you had a film you could just rewind to the formative moments of your life. Absent that, you have to make do with the next best thing, which are your family photos, letters, and significant objects. These are the primary source material of your life.

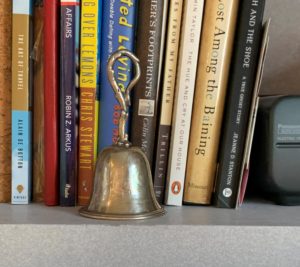

1. Using Heirlooms to Enlarge Memories

When I started my seriocomic memoir, Don’t Say a Word!, I knew I wanted to open with the scene at the Thanksgiving table, when my frightening, business-executive mother pronounced the words that are the title. My mother used a silver bell to summon the cook, a job taken by my former beloved nanny when I was twelve and no longer needed childcare. That bell is in my possession now. When I tried to get deeper into that opening scene, I put it on a shelf over my desk, where it would always be in sight.

Every day, I spent long minutes staring at it, imagining it beside my mother’s place at the table or in her hand. I remembered that particular Thanksgiving well because it opened up the mystery that led to my writing the book. But the bell took me back to the dinners of my childhood, the one time each day that I was in the crosshairs of my mother’s critical laser. Holding the bell, ringing it—which felt weirdly transgressive—brought back the anguish of watching my mother call my nanny to task, while having to hide where my sympathies lay. The bell opened up a rich vein of anxiety and guilt that was indispensable to the scene.

2. Getting to the Truth

Fleshed-out memories are essential for recreating the past and also for getting to the truth. As children, we do our best to make sense of what feels wrong, with whatever limited understanding we have at that moment. And so we often come to false conclusions––most commonly that we are responsible for things that were in fact entirely out of our control. These mistaken ideas we then carry through life. By revisiting the past, we can seek out these misconceptions and correct them with the knowledge we’ve acquired as adults.

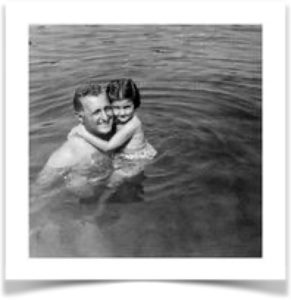

3. Using a Photograph as a Memory Aid

From a psychiatrist I used to see, I learned a technique that works wonderfully in this regard. If you spend a lot of time peering at an early photograph of yourself, you will find that you can connect with the state of mind of the child you were at that time. Through the expression and body language of your then self, you can recall how you were feeling, if not literally at that exact moment, then generally at that time in your life. And with an emotional connection to that child you can come your whole early world, with all its flavor and feeling. Such time travel can bring back all sorts of details, ones that may shift your sense of a family dynamic you’d never fully understood.

The second half of my book focuses on my father who, after my mother’s death, wanted my help in finding a housekeeper who would sleep with him, a crazy demand I could not get him to give up. I didn’t need help recalling my horror at his metamorphosis from the dad I loved to an apparent sexual harasser.

Studying this photo with him further reminded me of how much I owed him and of the father-daughter romance of my early imagination. It returned me to our repeated visits to the mummy room at the museum, where I’d hum “mummm, mummm” under my breath, while staring at the caskets of long-dead queens and holding my father’s hand, half-aware of the hum’s connection to “mummy,” the name I called my mother. The photo reminded me of how I’d always adored my dad and helped me understand why I’d felt compelled to make nice with the string of outrageous oddballs he hired during the years of his demented pursuit.

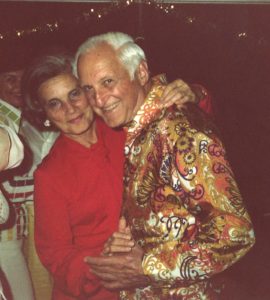

4. Correcting a False Narrative

Photos from the past can not only correct misunderstandings about yourself, but also about the important characters in your life and book. My parents fought continuously and furiously. They agreed on all the things couples normally fight about––friends, money, politics––but instead rose to the challenge of battling about nothing. They fought about the date of a trip on which they’d gotten a flat tire, the previous address of a favorite restaurant and whom they were meeting the night a certain joke was told, the pronunciation of a word. Their rage over these disputes led me to think that their marriage was unhappy.

But later, pouring through old photos after their deaths, I saw dozens of images of them dancing or dining or just gazing out at some scenery, in which their harmony and pleasure at being together is obvious. How could I have failed to see this when they were alive? Did I want to be fooled by the fighting? And what was this fighting really all about? A whole new inquiry opened up at this realization.

5. Saying Yes to Prying and Exposing

Among the papers that passed to me after my parents’ deaths were letters my father had written to my mother during World War II, eight years into their marriage. Initially, I resisted reading them; it felt voyeuristic, like looking through a keyhole into my parents’ private life. Whatever I learned could never be unlearned. I broke into a sweat when I opened the first crinkly letter to hear the voice of my father in his prime, 13 years younger than I was at that moment. The letters revealed an extraordinary embarrassment on both my parents’ parts about acknowledging their love for one another (which my father admitted to seeing as giving my mother a “fearful power” to hurt him). Seeing the insecurity of my intimidating parents made me realize I had totally misread them.

But could I write about this? Was it fair to show what my parents had spent their lives trying to hide? In my view, we write for the living, not the dead. And revealing people as more human just makes them more sympathetic. Only the full truth is worth writing––and reading.

Heirlooms, letters, and old photos are precious relics. Use them as a ticket back to the time before you were born and to the emotion-packed moments between then and now. Seek out the details that make you catch your breath or your stomach clench. Therein lies the hidden gold. Be brave. What you have been avoiding may prove to be essential to your book––and to a deeper, more constructive understanding of your own history.

Elizabeth Marcus grew up in Manhattan, the only child of a dentist and a Macy’s dress buyer, the Zeus and Hera of Apartment 2B. After escaping to Boston, she ran a small architectural office for 20 years, when she wasn’t traveling to far-flung places with her psychiatrist husband and rambunctious children. Eventually, she decided to concentrate on writing, which allows her to pursue the many, quirky questions that fascinate her: Why are butterflies called ‘butterflies?’ Why can’t she recall the taste of wines? Why are first-love memories so potent? Her essays have appeared in The New York Times and Boston Globe, on online sites like Cognoscenti, and in essay anthologies like Travelers’ Tales. “Don’t Say A Word!”: A Daughter’s Two Cents, in 90,571 words, is her first book. She posts essays related to the book at www.eLizWrites.com; she posts essays about everything else at www.archive.eLizWrites.com. She lives in Boston. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.