I almost fell into the trap recently. My protagonist, speaking of his brother, said, “That would be John going off half-cocked, Uncle, not me.” A nice evocative expression for someone who acts without thinking, right? The only problem is, the story is set at the beginning of the 14th century in western Europe. Guns didn’t appear in that part of the world until sixty years later; and the flintlock musket didn’t exist until about 1630, twenty years before the first recorded use of “cocked” in reference to a firearm. “Half-cocked” didn’t show up until the beginning of the 19th century.

Time to rework the dialogue.

We’re attuned to the notion of anachronism. No one would put a printing press in the Incan empire or a laptop in the 1930’s. But are we as careful when it comes to language? The issue isn’t unique to Historical Fiction, but it may be more glaring there. The last thing an author wants is a bad review stemming from a few unfortunate turns of phrase. So let’s take a look at how to recognize potential pitfalls and how to avoid them. Since most of us are writing in English, we’ll focus on that language, keeping in mind that similar linguistic evolution has occurred across the globe.

Know Your Risk

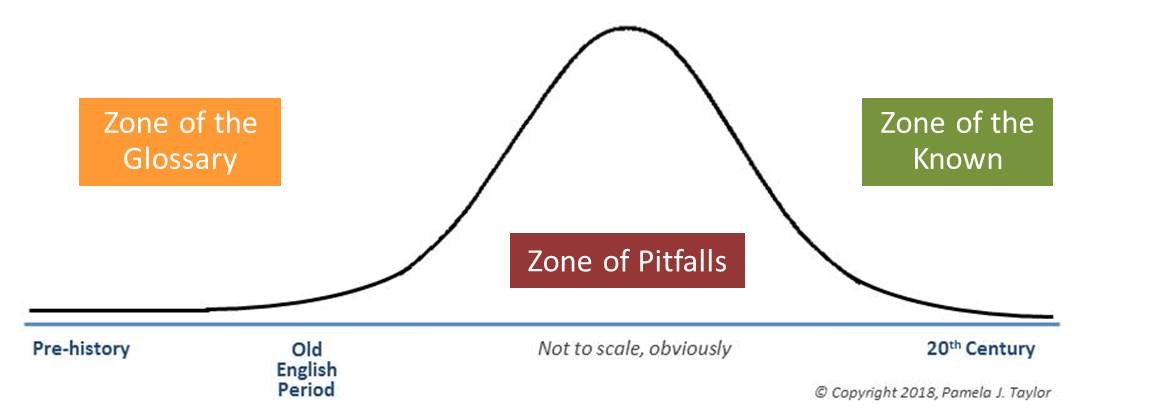

I like to think of the potential issues with linguistic anachronism as falling into three distinct zones.

The Zone of the Known: This is the area that both you and your readers will have some familiarity with the usages of your time period. Naturally, you wouldn’t have a 1920’s flapper saying “Cool!” or a WWII medic talking about PTSD. Getting the language right is no less important—it’s just more likely to be top of mind and easier to do.

The Zone of the Glossary: This spans a vast period from before recorded history to the end of the Old English period (in the first half of the 12th century). The actual language of those times is probably unapproachable to most readers. For a story set in that zone, you’ll likely choose a mix of modern forms and selective words from the period, and provide a glossary for the unfamiliar terms. An excellent example of this technique is Colleen McCullough’s Roman Republic series.

The Zone of Pitfalls: This encompasses 7.5 centuries in which our confidence in our knowledge of our time setting can easily conflict with our desire to create a narrative that flows well for a 21st-century reader. In this zone, we have to think about maintaining authenticity by seamlessly integrating the right language with the history and culture of the time.

The pitfalls may be subtle. Consider the word devil—it’s been with us for eons, right? So it’s probably pretty safe to have a character in any century saying, “It’s hopeless. I’m stuck between the devil and the deep blue sea.” Or, “If you don’t mend your ways, there’ll be the devil to pay.”

Not so fast. That nautical reference can only be traced to 1637. Since it was probably in common speech for some time before that, you could have your late-16th-century character utter those words, but think twice before putting them in the mouth of an early crusader. As for “devil to pay,” that phrase seems to have come into written language around 1711. So a character in Napoleon’s time could use it, but not one from the days of Charlemagne.

What’s a writer to do?

Obviously, you’ll rely on dictionaries and their documentation of earliest usages. My personal favorite is the Oxford English Dictionary. An online subscription isn’t cheap, but it may be worth it. Their date charts are excellent, references for phrases are quite helpful, and coverage extends to regional usage. Even an out-of-date version is fine; we’re not worrying here about words that have been added in the last 25 years.

Thankfully, we live in the era of internet search. Even simple search phrases will reveal a wealth of information—and some surprising things you might never have expected to find an authoritative source for. When I needed some sexual slang for one of my bawdier characters, I found an amazing site with timelines of such slang going back to the 13th century. I could then triangulate with the dictionary to get it right for my era.

Follow links from one source to another. You’ll know soon enough if you’ve gone down a rat hole or a path to linguistic riches. And the more sources that agree, the higher your confidence in what you’ve found.

We know that language evolves with human understanding. Researching a “thing” of your era is another valuable pointer. Need to write about canons? Check out the Wikipedia article. You’ll discover what devices were in use at the time of your story and what they were called in different countries, then cross-reference with the dictionary for added verification. When I had my “half-cocked” moment, I found a great timeline on the PBS History Detectives site. Will your characters be dancing? Google it. You’ll find the right dances for your time period—and, often, videos of the dances being performed. All this will lead you to the right language.

Don’t forget that the blurring of eras in popular or even scholarly understanding also informs your search results. So if searches for things in your time period are yielding results that are decades or centuries too late, back up and look for the preceding era. You can then follow the usage trail to what you need.

Permission to contract

Linguistic anachronisms also extend to style. Consider, for example, the use of contractions. Many authors eschew contractions in favor of more formal speech, perhaps on the theory that written and spoken language in past times was more stilted and formal than today—and some things certainly were—and perhaps because, at various times, scholars and literary lights have frowned upon their use.

So are contractions anachronistic? Not at all.

Old English, Old Spanish, and the predecessor languages to Old French all used contractions. By Shakespeare’s time, contractions in English were widespread. The Bard used them profusely in his plays—often, of course, to get the meter right. But one must assume they were well known, else how would playgoers have understood what was being said on stage?

And how often have you just supplied the contractions yourself as you read a passage, mentally articulating “It’s not a good time for a talk” when what’s actually on the printed page is “It is not a good time for a talk”? I certainly do it frequently.

Knowing this leaves you free to make stylistic choices that suit the tale.

Proper or Pragmatic?

Which brings me back to the title of the article. As important as the right language is, pragmatism is sometimes appropriate. Investigating the mid-14th-century term for the conveyance we call a wagon, I discovered it was called a “wain” at that time—first-use dates for “wagon” in English are early 1500s. Which left me with a decision. Write some prose introducing my readers to the term “wain” by describing its use to haul goods to market and collect grain from the fields? Or take the view that “wagon” came into speech well before written use, and fudge a bit on authenticity?

The decisions you make will be influenced by the style of your story. Is it pseudo-documentary, sticking close to known events and heavily peopled with historical figures? Does it have broad descriptive passages well-suited to the necessary explanations? Have you established a pattern of using only the most accurate and authentic term? If so, you’ll likely choose “wain.”

In my case, the story was time-authentic, but the characters were all fictional, and broad descriptive passages were not a feature of the narrative. The need for the word “wagon” was merely incidental to the story. So I made the decision not to disrupt the flow by sending my reader scurrying for a dictionary to find out what the heck a “wain” might be. If my tale had been set in the 10th century, however, . . .

The point, of course, is not to be pedantic about linguistic anachronism but to be mindful of it. Strive for authenticity, avoid glaring breaches, and ultimately, make choices that enhance your reader’s experience.

Pamela Taylor’s inspiration for her first book turned out to be that final straw that pushed her to leave the corporate world behind for the world of words and imagination. Now an author and an editor, she loves helping others polish their stories almost as much as she enjoys writing her own. She’s a member of the DFW Writers Workshop and the Editorial Freelancers Association and is in her second year on the judges panel for the Ink & Insights Contest. You can learn more about her books at secondsonchronicles.com, and about her editing services at editing4you.com.

Pamela Taylor’s inspiration for her first book turned out to be that final straw that pushed her to leave the corporate world behind for the world of words and imagination. Now an author and an editor, she loves helping others polish their stories almost as much as she enjoys writing her own. She’s a member of the DFW Writers Workshop and the Editorial Freelancers Association and is in her second year on the judges panel for the Ink & Insights Contest. You can learn more about her books at secondsonchronicles.com, and about her editing services at editing4you.com.