One of the things I always tell my students is that the writer’s job is to tell the Truth with-a-capital-T. It’s not always about getting the facts straight, because depending on what you write, there’s wiggle room to shape the facts so that the story rings true. That said, it is the writer’s responsibility not to sit idly by when there is truth that needs speaking.

Last week was the National Book Awards and two things happened that set Twitter on fire. The first was Ursula Le Guin’s beautiful acceptance speech after being honored with a lifetime achievement award. In this speech she warned that “hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now…. We will need writers who can remember freedom. Poets, visionaries–the realists of a larger reality.” Click the link to read a transcript of the speech in its entirety. It’s short and quite powerful.

The second thing that happened was that MC Daniel Handler (AKA Lemony Snicket) put his foot in his mouth by making racist jokes not once or twice, but THREE times during the ceremony. The worst insult of the lot was at the expense of author Jacqueline Woodson who won the National Book Award for young people’s literature with her book Brown Girl Dreaming. I won’t repeat any of the jokes here because I believe repeating such words (even to criticize them) only gives them more power. If you’re curious, just scroll through the Twitter hashtag #NBAward and you’ll get the gist.

I want to talk about our responsibility as writers and how both Le Guin’s words, and Handler’s words relate to this responsibility. What set most people off about Handler’s jokes was that they were racist, but the problem goes deeper than that. We’re not living in a time of slavery in the USA anymore. We don’t have segregated bathrooms, water fountains or seats on the bus. Racism–or any “ism” for that matter–is more subtle these days, but no less insidious.

The problem with jokes like Handler’s at the National Book Awards is that they separate people into categories according to race, gender, religion, etc. and that they put the label front and center and shove the human being into the background. These labels only serve to push human beings into neat little boxes; they are like a shorthand and they over-simplify the beautiful complexity of humanity. When we use words that are racist, or sexist or any other “-ist” it’s like we’re saying someone: “I don’t have time to see you as a full, complex human being, so I’m just going to slap a label on you and call it a day.”

As writers it is our duty NEVER to use such shorthand. Why? Because it wouldn’t be the Truth. Humans are not the color of their skin, the language they speak, the amount of money in their bank account, and so on. Humanity is messy, and complicated, and sometimes even contradictory.

In her speech, Ursula Le Guin upheld the responsibility of a writer: she told the truth. She reminded us that as writers we are “realists of a larger reality” and that our job will be to shine a spotlight on that reality. Handler’s words evaded the Truth, not because they were factually incorrect but by making these jokes, he put the label at the forefront and the humans into the background. As a person, he should have followed that old adage “if you don’t have something nice to say…” but more importantly, he failed his responsibility as a writer because he obscured the full human truth with labels and shortcuts.

There’s a movement now called #WeNeedDiverseBooks. It’s a Twitter hashtag, and a website, and they raise money to help bring more diversity to literature. Handler’s jokes made abundantly clear that a lack of diversity in publishing and books is still a huge problem. Interestingly enough, Handler chose to atone for his jokes by matching donations to #WeNeedDiverseBooks for one day. (My opinions on that score are a matter for a whole other discussion.) This organization is making great strides to address this issue and I applaud their efforts, but we need to do more. Just by labeling books as “diverse” automatically puts them in a category that’s separate from the rest of literature. Increasing diversity in literature is the necessary first step because we can’t show a full picture of humanity if essential pieces are missing from the story. But it is also only the beginning.

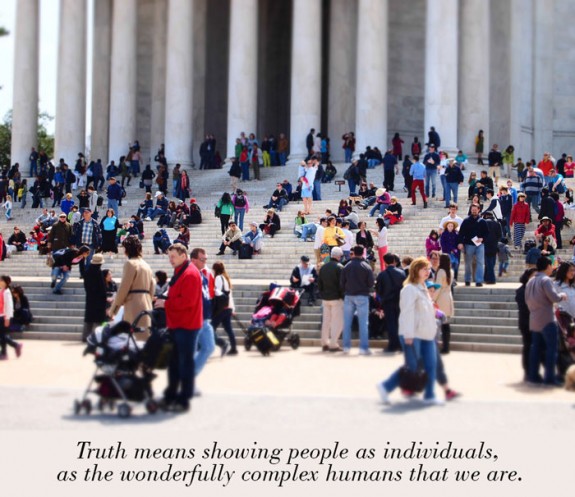

Once we’ve filled in those gaps, once we have more stories in our literary culture that reflect the diversity of our society, then we have to take another step and this one is even more important than the first. Inclusion is not enough. We have to tell the Truth behind the labels. We have to show people as individuals, and while they might represent diverse groups, they are not defined by those groups. It’s not so much that #WeNeedDiverseBooks. What we need are #BooksThatTellTheTruth. This Truth is not about shortcuts and labels; it’s not about pigeon-holing people and sorting them into neat categories.

In eleventh grade, we had a unit in our history class called SEED (Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity). One of our assignments was what I now call the “bubble” exercise. The teacher handed out a sheet of paper with five circles. We were supposed to put our names at the center of the page, then in each of the “bubbles” we were supposed to list a circle or group that we identified ourselves with. After taking a few minutes to fill out the sheet, we went around the room and everyone shared what they wrote down.

This was one of the most embarrassing moments of my life because as each of my classmates read what was on her sheet, I realized I had done the exercise completely WRONG. The “bubbles” that my classmates listed were things like their gender, ethnicity, social class, etc. I on the other hand, had listed the people in my life like: my family, my school friends, my music friends, my martial arts friends… When I finished reading what I wrote, I said: “I guess I did the exercise wrong. I didn’t even write down that I’m Brazilian.” The teacher gave me this funny look that I didn’t quite understand at the time, kind of a half-smile like she was in on a secret joke that no one else in the class got.

That day at lunchtime, I overheard some of my classmates making fun of my answers to the exercise. Didn’t I understand that the whole idea was to be aware of my identity? How ignorant was I that I didn’t think to mention my dual-nationality? Apparently I couldn’t even label myself correctly (in fact, I was unable to label myself at all).

A year and a half later, understood my teacher’s secret joke. My guidance counselor let me read the recommendation letters that my teachers had written to colleges. One line jumped out at me and it was from that history teacher: “Gabriela refuses to be pigeon-holed, and she’s not afraid to tell the truth.” That was when I realized that point of that “bubble” exercise wasn’t to list out which circles we belonged in, but to challenge the very purpose of those circles in the first place.

As writers, we are given the privilege of our words being allowed to enter another person’s mind and to influence what they think and feel. Essentially, our words occupy someone else’s mental real estate and can influence and affect other human beings. This is a huge responsibility, and we must recognize as such. We must also be aware that our words are shaped by our experiences, that “rules” are often shaped by the contexts in which they exist.

We might all interpret Ursula Le Guin’s words in our own way, and our understanding of her powerful speech will be different depending on our individual experiences and who we are as human beings. However the heart of her speech remains the same across the board. Her words express hope and empowerment to writers. Handler’s words, on the other hand–whether we interpret them as racist or not, as mean-spirited or just plain stupid–they were words spoken in an attempt to prop one human being up while putting others down. No matter what context you put them in, the meaning at its heart is still the same.

Words are powerful, and writers have the opportunity to use that power for good. It’s our job to show the world as it really is, in all its beautiful complexity. It is our job to tell the Truth. Anything less than that is not enough.